Sign up for Unlocking the World, MathHotels.com Travel’s weekly newsletter. Obtain information on locations, along with the newest updates in air travel, cuisine, and accommodation options.

Nowadays, air travel using jet engines is something we often overlook. We have become accustomed to the rush of speed on the runway that pushes us back into our seats, the instances when we break through dark clouds into clear blue skies, and the soft beeps reminding us to secure our seatbelts. Additionally, we are used to reaching our destination safely.

But commercial jet travel has only been around for 73 years. Britain’s late Queen Elizabeth II was the reigning monarch when the de Havilland DH106 1A Comet G-ALYP departed from London Airport — which was then called Heathrow — at approximately 3 p.m. on May 2, 1952, transporting the world’s first paying jet passengers. Over the following 23 hours, with five stops along the journey, it traveled 7,000 miles south to Johannesburg.

That flight represented a major advancement in both comfort and speed when compared to the best propeller planes of its time, such as the Lockheed Constellation. The persistent shaking and the loud noise from piston engines were now a thing of the past. The world had abruptly and permanently stepped into the jet age.

The first company to develop a jet plane and establish itself in the skies, surpassing American competitors such as Boeing, was the British aviation firm de Havilland. This lead, however, would not endure: the initial Comet DH106 had a short period of dominance before a series of disasters caused its entire fleet to be grounded and subsequently either tested until destruction or left to decay.

Many years later, the only way to get a sense of what it was like aboard those initial Comets is by watching faded black-and-white movie clips or colored promotional photographs featuring happy families seated on DH106 1As.

Or at the very least, until recently, these images were our only source. Now, a group of dedicated fans has carefully reconstructed one of those early jetliners — with exciting outcomes.

‘A beautiful sight’

unknown content item

–

The de Havilland Aircraft Museum is among the world’s less well-known collections of aviation relics. Situated in a stretch of farmland and open space northwest of London, near the perpetually busy M25 motorway that surrounds the UK’s capital, it can be easily overlooked. There are signs, but they direct visitors to a small path between hedges that appears to lead to a farmhouse or a cul-de-sac.

Certainly, proceed down the road, and the first impressive view is a large old manor house — Salisbury Hall, constructed in the 16th century and previously the residence of Winston Churchill’s mother — that typically manages an agricultural base. However, continue forward, take a turn, and the museum becomes visible: a field covered with the remains of old airplanes and a set of hangars that suggest additional wonders lie within.

The location holds a significant place in aviation history. It was here, during World War II, that a regional aircraft company, established by British aviation pioneer Geoffrey De Havilland, started developing and testing the DH98 Mosquito, a distinctive wooden-structured fighter plane known for its remarkable speed. Following the war, in the late 1950s, a local businessperson took advantage of the site’s heritage to establish Britain’s first aviation museum.

A vibrant yellow Mosquito, identified by museum employees as the sole surviving World War II prototype aircraft, is a standout display at the contemporary de Havilland museum. It has been meticulously restored, featuring its bomb bay doors fully open and its substantial propellers, connected to Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, extending forward.

Other de Havilland aviation icons, both for civilian and military use, are on exhibit. In the corner of the Mosquito hangar, there is the frame of a Horsa glider, a non-powered aircraft from World War II that was pulled into the sky and utilized to transport soldiers and equipment behind enemy lines.

In the following hangar — where dedicated volunteers, who sometimes exceed the number of visitors on certain midweek days, are engaged in extensive restoration work — there is a DH100 Vampire, a single-seat fighter that marked de Havilland’s first jet aircraft. This unusual-looking plane, featuring a twin-boom tail, was also developed at Salisbury Hall.

But the clear standout in the museum’s biggest exhibition area is the de Havilland DH106 1A Comet. For those passionate about commercial jet aircraft and how they have developed into the sophisticated engineering marvels that now traverse the skies, this is a must-visit destination.

Although its wings are absent, the Comet stands out with its body painted in authentic Air France style, featuring a chrome-like landing gear, a shiny white roof, a seahorse emblem with wings, and the French flag.

“It’s a beautiful-looking aircraft, even after all these years,” says retired Eddie Walsh, a museum volunteer leading the effort to restore and maintain the DH106.

Walsh explains that this specific aircraft wasn’t always in its current state. When the museum received it in 1985, it was essentially just a bare metal frame — the remnants of the fuselage. “It looked very depressing. Every part of it had been retrieved, so the original exterior was in extremely poor condition.”

‘Utter nightmare’

Carefully, the volunteers gradually started bringing it back to its former aeronautical splendor — and now, the aircraft is roughly how it would have appeared almost three quarters of a century ago, except for the wings.

“We’d really like to have the wings too, but the wings would almost fill up the entire amazing museum,” says Walsh.

This is unfortunate, as the Comet’s wings were also a sight to admire. Unlike most later commercial airplanes, the aircraft featured its engines, four de Havilland Ghost turbojets, seamlessly integrated into the wing rather than housed in pods beneath it.

Although they were visually appealing and technologically advanced, the fuel-hungry engines failed to perform adequately, making it difficult for the Comet to take off. This led to pilots sometimes initiating ascent too soon or exhausting the runway length. The resulting crashes were terrible, but the underlying design and engineering flaws that ultimately caused the Comet’s downfall were even more severe.

Prior to becoming a symbol of danger, the Comet was an example of the luxurious potential of travel. At the back of the plane, a staircase leads up to the tail section. Entering through the door is like traveling back into the history of air travel. The interior of the aircraft has been carefully restored by Walsh’s team, with every small detail accurately recreated.

Initially, there were the restrooms. In contrast to the single-gender bathrooms found on modern aircraft, the original Comet featured separate male and female toilets — the men’s area equipped with a urinal, while the women’s included a chair, table, and vanity mirror.

In the primary cabin, half of the aircraft has been restored to its original design, featuring cozy rows of twin seats covered in swirling blue fabric that complements the red curtains’ pattern. Every seat offers ample legroom, along with chrome cup holders and — since it was constructed in the 1950s — ashtrays for smokers, who, despite the elegance, would have made flights an “absolute disaster,” according to Walsh.

The seats offer a view through big rectangular windows, a characteristic of the first Comet aircraft — sometimes incorrectly blamed for the plane’s structural issues and later replaced with more rounded openings in subsequent models.

During meal times, the cabin crew handed out bulky wooden trays for meals that were served on real plates and eaten with proper utensils. Above, there are no overhead luggage compartments, but the museum has used 3D printers to create molded light fixtures, each featuring a red button to call the “steward.”

An almost impossible task

The precision of the cabin replica makes it simple to envision life aboard the Comet, with actual clouds passing by outside, rather than the static ones painted on the wall of the de Havilland Museum hangar. It isn’t vastly different from the aircraft we travel in today, but it was clearly designed to provide a more luxurious air travel experience.

That experience needed to be made pleasant. Indeed, the Comet featured smooth jet engines and a pressurized cabin enabling the aircraft to fly 40,000 feet, well above severe weather conditions, and it was indeed quicker than propeller planes, but its maximum range of 1,750 miles (2,816 kilometers) was significantly shorter than that of previous passenger services.

Extended trips, such as the initial flight to Johannesburg, moved more quickly in the Comet, yet since they needed to be split into several segments, overall travel times remained longer compared to today’s standards.

Closer to the front of the Comet, the first-class section of the cabin more closely resembles a contemporary private jet rather than the premium seating found on modern airplanes. In this area, two sets of seats are positioned opposite each other around a wooden table — a design intended for stylish families.

This was the peak of luxurious travel. The promotional photographs from that era depicted travelers dressed in elegant gowns and well-fitted suits, typically enjoying drinks or indulging in extravagant meals. One notable, yet highly unrealistic, picture shows a family happily observing a child constructing a house of cards on the first-class table. Even with quieter jet engines, those cards would not have remained standing for long.

The amount of passenger wealth shown in the images was correct, according to Walsh.

He adds, ‘It was extremely costly.’ ‘I mean, with today’s travel, you can find seats for almost nothing. But back then, you had to be someone with considerable wealth to actually fly anywhere—especially on the Comet.’ A single ticket on the Comet’s inaugural flight to Johannesburg was £175—approximately £4,400, or nearly $6,000, by today’s standards.

Beyond the first-class area, there is a compact galley kitchen featuring a hot water heater and a sink. There is also a storage compartment where the large suitcases and steamer trunks of affluent passengers were secured by a weak piece of netting that likely struggled to keep them in place during turbulent moments.

Then there’s the flight deck — once more, carefully recreated by the museum’s team, right to the panel of analog dials and switches that would have been recognizable to the Comet’s pilots, many of whom gained experience flying World War II military planes. In this area, the intricate arrangement suggests the significant work that has been put into restoring the aircraft.

Recreating it, according to Walsh, was “bordering on an impossible task.”

How in the world do you begin that? It’s one of those tasks where you might just stand there, puzzled. ‘Where do we find the pieces? How do we assemble them? How do we arrange them? How do we illuminate them?’ But in the end, it turned out really well.

Too high, too fast, too early

Behind the pilot and co-pilot seats, there are additional chairs designed for a flight engineer, whose role was to track fuel usage and oversee the aircraft’s mechanical systems, as well as a navigator who relied on maps, paper, and a pencil to chart the course. The navigator would also utilize a periscopic sextant to look through the aircraft’s roof and determine location by observing the sun and stars—similar to how sailors of the past navigated at sea.

Although this may have seemed outdated in comparison to the digital systems found in modern passenger aircraft, the Comet was considered advanced in 1952.

It moved quicker, reached greater heights, and offered a much more comfortable ride,” Walsh remarks. “It was a breakthrough — the Concorde of its time.

However, it did not maintain that position for long.

“Too high, too fast, too soon—that was the issue,” remarks Walsh.

Back in the main cabin of the de Havilland Museum’s Comet, one side of the plane has been removed to expose the fuselage’s exterior and the components surrounding the aircraft’s windows, along with the rivets that secure them.

The cabin wall was the most deadly of the Comet’s many shortcomings, as the plane rapidly shifted from a showcase of creative engineering to a chilling example of design malfunction.

On March 3, 1953 — less than a year after its initial scheduled flight — a Comet made history as the first commercial jet aircraft to be involved in a fatal accident when a Canadian Pacific Airlines flight crashed into a drainage ditch during takeoff, resulting in the deaths of five crew members and six passengers. Just two months later, another crash during takeoff in India claimed the lives of all 43 individuals on board.

The situation deteriorated the next year. On January 10, 1954, a Comet disintegrated mid-flight during a journey to Italy, taking the lives of 35 individuals aboard. This event triggered concerns about possible structural issues with the plane, leading to a global suspension of operations for several weeks. Shortly after services resumed, another in-aircraft disaster occurred on April 4, 1954, resulting in the deaths of all 21 passengers and crew.

Following that, the Comet 1A was permanently taken out of service.

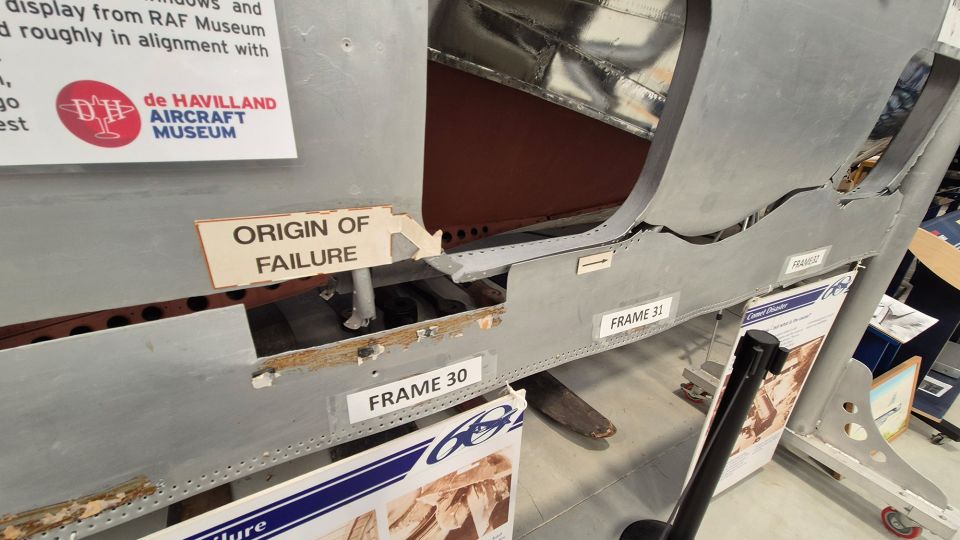

Subsequent water tank tests on Comet airframes ultimately determined that the aircraft’s exterior could not endure the repeated pressurization and depressurization necessary for high-altitude flight. Cracks emerged near bolt holes and rivets, leading to sudden ruptures in the fuselage around openings like a cargo door or rooftop antenna.

Beside the Comet, the de Haviland museum exhibits a portion of the fuselage that was subjected to extreme testing until it failed. This serves as a tribute to the dedication of aviation investigators who aimed to uncover the aircraft’s critical weaknesses, yet it also acts as a troubling reminder of the heavy price paid in the pursuit of advancing aviation.

Although the Comet 1A did not operate commercially again, it led to subsequent models that achieved success, featuring more advanced Rolls-Royce jet engines and reinforced fuselages. However, when the Comet 4 began service in 1958, it encountered competition from Boeing’s 707 and the Douglas DC-8, which were seen as more efficient and preferred by airlines at that time.

De Havilland’s prominence in the commercial aviation sector had declined. The company was eventually acquired by another major British aviation firm, Hawker Siddeley, and the brand largely disappeared — although a former subsidiary, de Havilland Canada, continues to operate.

The Comet may have vanished from the skies, but its impact remains evident in the airplanes we use today. The advancements made on the 1A, along with the fatal errors that accompanied it, contributed to the development of safer subsequent aircraft.

Without someone initiating everything and getting something running, obviously everyone else won’t follow,” says Walsh. “Therefore, it requires someone to innovate the idea, develop it, and get it functioning to demonstrate that an aircraft, specifically a jet aircraft, can take off with passengers aboard.

The Comet is known for the issues it faced, which is somewhat unjust, as it was actually a pioneering creation for its era.

For additional MathHotels.com updates and newsletters, sign up for an account atMathHotels.com